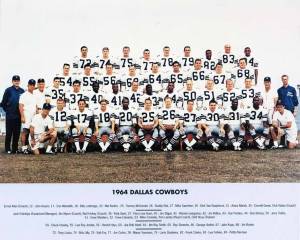

My attachment to and enthusiasm for the Dallas Cowboys undoubtedly peaked in the mid- and late 1960s. That was when the team played in the antiquated Cotton Bowl and pro football had yet to become the multi-billion-dollar enterprise it is today. Tom Landry was lifting them from a hapless expansion club to the elite of the NFL, the media lionized the players, and it helped us to put the Kennedy assassination aside—at least temporarily. That was an exciting time, especially for a young, impressionable and sporting Dallasite. The Cowboys are still my favorite team, but I would be hard pressed to name a current player besides quarterback Tony Romo. I’m pretty sure the coach is Jason Garrett. I could not tell you the name of this year’s first-round draft choice to save my life.

My attachment to and enthusiasm for the Dallas Cowboys undoubtedly peaked in the mid- and late 1960s. That was when the team played in the antiquated Cotton Bowl and pro football had yet to become the multi-billion-dollar enterprise it is today. Tom Landry was lifting them from a hapless expansion club to the elite of the NFL, the media lionized the players, and it helped us to put the Kennedy assassination aside—at least temporarily. That was an exciting time, especially for a young, impressionable and sporting Dallasite. The Cowboys are still my favorite team, but I would be hard pressed to name a current player besides quarterback Tony Romo. I’m pretty sure the coach is Jason Garrett. I could not tell you the name of this year’s first-round draft choice to save my life.

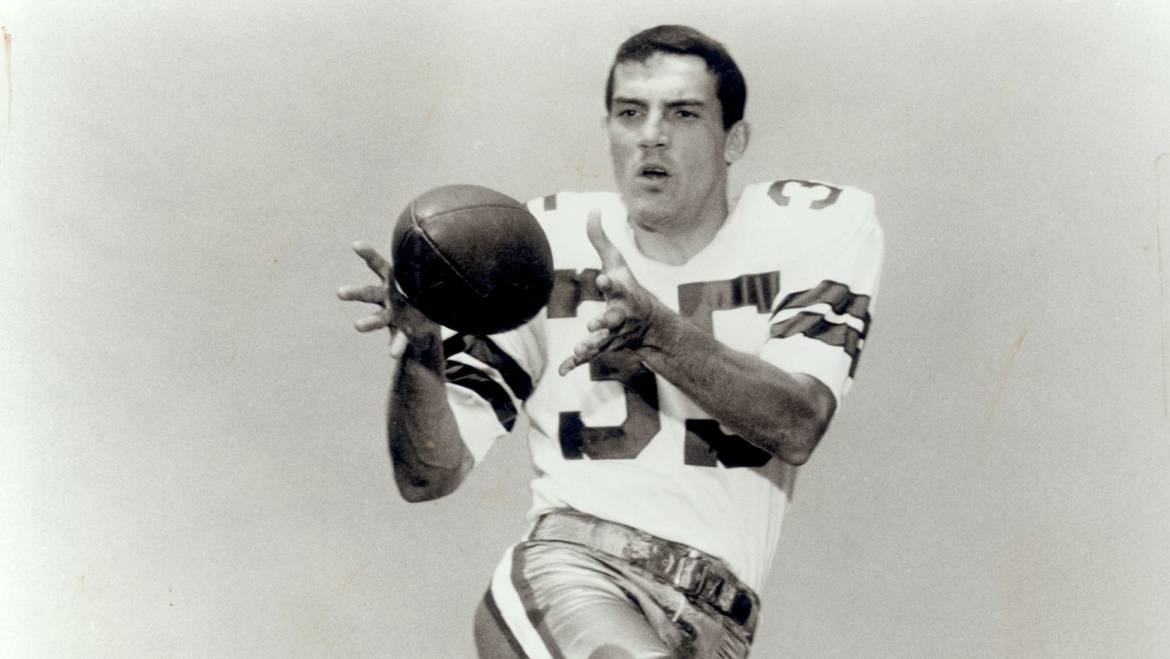

Pete Gent was a hard-working player but nobody would list him among the Cowboys’ stars in those days. As a flanker and tight end, he caught 68 passes and scored four touchdowns between 1964 and 1968. He played just long enough to earn a modest pension from the NFL Players Association, and he came to need it.

As is well known, Gent did not play football in college. He was a fine basketball player at Michigan State, and the Cowboys signed him as a free agent. Although not especially fast, he had size (6′ 4″) and soft hands so he made the team. Landry and general manager Tex Schramm probably rued the day because Gent went on to form an unholy alliance with quarterback Don Meredith as they challenged the authoritarian ways of their bosses. Gent grew his hair long, smoked pot and indulged in other extracurricular activities. It was the sixties, after all.

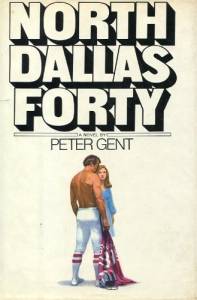

NDF

None of this would have mattered if he had not written North Dallas Forty in 1973. Although fictional, it was based on first-hand information about the gritty realities of life in pro football. Gent’s novel was  made into a movie six years later. While book and film were enormously successful and earned lots of money, not much of that went to Gent. He wrote other books in later years, but they never came close to the heights of North Dallas Forty.

made into a movie six years later. While book and film were enormously successful and earned lots of money, not much of that went to Gent. He wrote other books in later years, but they never came close to the heights of North Dallas Forty.

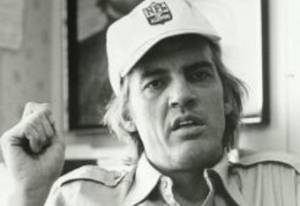

In 1983, Gent was residing in Wimberley, a picturesque little town outside of Austin. He was living off the good graces of a man named Sonny Gold who served as justice of the peace and ran a colorful agglomeration of businesses, one of which was a used-car dealership. With a new book (The Franchise, essentially a retread of NDF) out, he was happy to give me a series of interviews for an article I was writing about him in Third Coast magazine. Gent was quite an interesting guy, an outrageous guy who spoke in a loud but articulate manner. I have to say I enjoyed meeting and coming to know a former Cowboy and hearing about Landry, Meredith, Bob Hayes, Lee Roy Jordan, Mel Renfro and other big names from those days.

Pete’s problems

Gent’s life was a mess. He was in the middle of a nasty divorce—I made a young journalist’s mistake of writing about it in the article—and was hard up for money. Like most former pro football players, he was paying the price for earlier glory in the form of constant pain and premature aging. During those five years in the NFL, he had suffered cracked vertebrae, broken ribs, broken fingers and a broken nose. We talked about the physical pain that is an integral part of life for ex-football players and how they deal with it.

We covered a lot of things, Pete and I did, and so when the Third Coast article came out, I gave him a call to get his response. It seems he was not pleased. He blistered my ears with two minutes of profanity, insults and threats. I had been wrong, evidently, in writing a piece that was candid and balanced. I had not been impressed by The Franchise and said so; Gent thought I should have called it the finest piece of literature of the decade, if not the century. I said he had been a journeyman ball player; he had a much higher estimation of his athletic skills. I portrayed his current situation accurately; he viewed that as a low blow. I was disappointed that he, a man who considered himself a teller of unvarnished truth, expected me to write a puff-piece. Had he let me get a word in edgewise, I would have told him that I deal in facts and reality, not dreams and fantasy.

Gent had been 41 when we met. One line from North Dallas Forty had a character moaning because retired players’ pensions could not be collected until they reached the age of 55, “the old double-nickel.” He found it curious since doctors had determined that the average age of former players at death was 55.

Gent had been 41 when we met. One line from North Dallas Forty had a character moaning because retired players’ pensions could not be collected until they reached the age of 55, “the old double-nickel.” He found it curious since doctors had determined that the average age of former players at death was 55.

For no apparent reason, I thought of Gent on October 1, 2011. I wondered whether he was still alive, so I went to Google. Strange coincidence. I learned that, in fact, he had died the day before—September 30. He succumbed to nature’s demands due to an unspecified pulmonary disease. The obituaries and tributes, of which there were many, stated that Gent had been living in his family home in Bangor, Michigan. He was 69, having collected his NFl pension for 14 years.

Almost to the end of his life, Gent was a favorite of reporters who wanted quotes about the pros and cons of playing in the NFL. No one could summarize the suffering and sacrifice involved better than he. But Gent made clear that he had no regrets. The thrill of going out on the field with his teammates in front of 70,000 fans, catching a long pass and winning a big game were things few get to experience. He felt very grateful to have had that opportunity.

4 Comments

What happened to Carter ?

Ms. Hochman refers to Gent’s son, Carter. I mentioned him in the Third Coast article, but not here. The kid (now an adult) is of no consequence, and thus I made no reference to him. Who cares what happened to Carter?

I was a fan of Gent’s and the Cowboys from the same time you were. Read his book and saw the movie. Nick Norte was an inspired casting choice. I think they had similar issues. I met his ex-wife in Austin, during the making of Blood Simple, she was dating a local involved in the production, who I knew from having several friends with bit parts or working production. She was still angry with him and said it was tough living with a manic-depressive personality. With some of the hits he took, it may have been concussion related.

I have often wondered if he had regrets–all the health problems, etc.

Add Comment