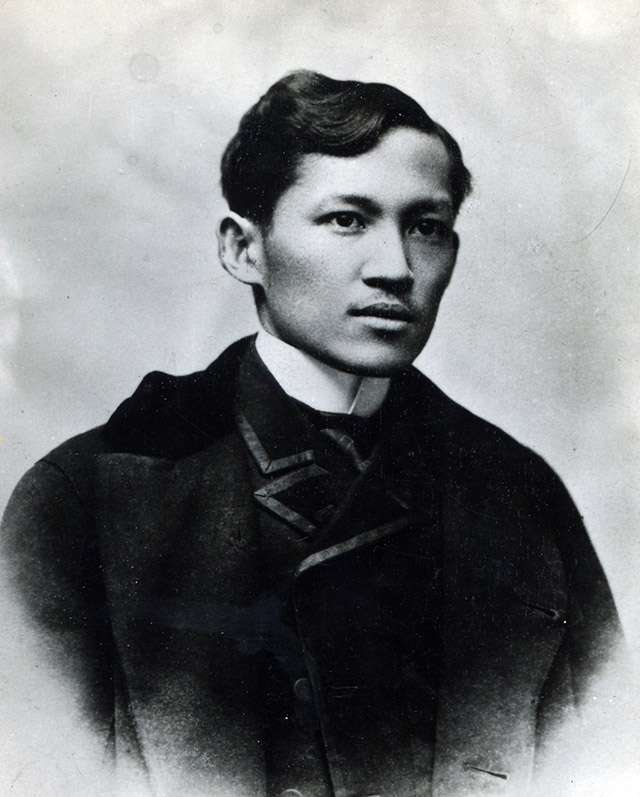

I spent four days in Manila, the Philippines during the summer of 2007. And while there, I was able to see a few spots of historical interest—Malacanang Palace, Manila Bay, the 400-year-old cathedral, Intramuros and Fort Santiago among them. It was at the latter site that I first learned about Dr. Jose Rizal. Oh, I was vaguely aware of his name before but I could not have told you who he was or why his life (1861−1896) was significant. After reading a 531-page biography, I am now somewhat more aware.

Born into a wealthy family in Calamba, Rizal had a prodigious intellect. He traveled to Europe for his medical education, making friends with Filipino expats and scholars in Spain, France, Germany and Belgium. Not only was he a sociable man, he had progressive ideas that the Spaniards—colonizers of the Philippine islands since 1565—found threatening. Rizal wrote two novels, Noli Me Tangere and El Filibusterismo, both of which called into question the legitimacy of Spain’s continued rule of the archipelago. Many indigenous revolts against the Spanish had arisen, and all had been mercilessly crushed. While I do not wish to add another chapter to the “Black Legend” of Spain, that country does seem to have outdone the English, French, Portuguese and Dutch in its colonial grasping. The Spanish in those centuries were all about domination and extraction of wealth. Remember the Manila Galleons, the three-way trading expeditions that linked Mexico, the Philippines and Spain? The benefits were overwhelmingly in favor of the Spanish. In fact, I would tentatively assert that many of the problems that plague both Mexico and the Philippines today—such as endemic poverty and corruption—derive from their long years of submission to Spain.

Rizal was living in Madrid in 1892 and had been warned not to return to the Philippines. He wondered why. His books did not advocate revolution but reform—human rights, that the Philippines be made a province of Spain, that it have representation in the government, the removal of abusive friars, land redistribution and so on. Rizal did foresee a time when the Filipinos would be fully self-governing, but not yet. (Others, such as the Katipunan, disagreed. Its members had begun to conduct guerilla activities with the express intent of overthrowing the Spanish.)

Was he naïve, or was Rizal bold and full of love for his country? Either way, he made up his mind to come home. Soon after he did, the authorities arrested him and sent him into a four-year internal exile in the remote city of Dapitan. As events unfolded, Rizal was brought back to Manila, charged with rebellion, sedition and conspiracy, and put on trial. He was convicted and given the death penalty. In the hours before his execution by a firing squad of Filipino soldiers (with a backup force of Spanish Army troops ready to shoot them if they failed to carry out their duty), he wrote an achingly beautiful poem entitled “My Last Farewell,” the initial stanza of which reads:

Farewell, my adored Land, region of the sun caress’d,

Pearl of the Orient Sea, our Eden lost,

With gladness I give thee my Life, sad and repress’d;

And were it more brilliant, more fresh and at its best,

I would still give it to thee for thine welfare at most.

I saw Rizal’s death cell in Fort Santiago, and I solemnly followed his footsteps—painted in white—to the courtyard where the sentence would be carried out on the morning of December 30, 1896. The Philippine revolution, which had been raging since earlier that year, picked up speed. The Spanish were soon out, bringing to an end more than three centuries of colonial rule. Of course, the picture is not so tidy since they were replaced by a very different kind of economic, political and military force—the Americans. Some wag once characterized Philippine history as 300 years in a convent followed by 50 years of Hollywood. Independence finally came on July 4, 1946.

A few days after my visit to gloomy Fort Santiago, I was in the town of Guihulgnan in Negros Oriental. Facing the Tanon Strait was a statue of Rizal, but I found it less than enthralling. It was in a state of trashed-out deterioration; weeds grew up through cracks in the cement. Not only is the country chock full of Rizal statues, there is also a Rizal Park in Manila, a Rizal Province, a Jose Rizal Institute, a Jose Rizal University and a multitude of Jose Rizal elementary, middle and high schools. December 30 is Rizal Day in the Philippines, and his likeness has graced several of the country’s banknotes. Noli Me Tangere and El Filibusterismo are still required reading for most students. Nevertheless, the crumbling statue of him in Guihulgnan gave me the uneasy feeling that modern citizens of the Philippines have to some degree forgotten their national hero.

Add Comment