Kathleen Monte, my main squeeze from the summer of 1989 to early 1993, had an easy life. Her father had left her an inheritance that approached $1 million. On top of that, her job at IBM paid well. She lived in a house in northwest Austin that may not have been a palace but was still quite comfy. As my bungalow south of the Colorado River was unsuitable, we decided to hold a party there. It would take place on New Year’s Day, 1991.

Restoring order

Before the 1990 University of Texas football season began, Coach David McWilliams and his biggest stars (quarterback Peter Gardere, running back Phil Brown, receivers Kerry and Keith Cash, offensive lineman Stan Thomas, defensive lineman Shane Dronett, linebacker Brian Jones, and DBs Stanley Richard and Lance Gunn) posed for a poster. In a desert setting, McWilliams et al. wore stern faces, cowboy  boots and dusters. It was labeled “They came to restore order to the Southwest.” The sly reference is not to that region of the USA but the now-defunct Southwest Conference. “Order” meant that UT, the biggest and richest school in the SWC, should be king of the hill. But the Longhorns, to my dismay, had fallen to also-ran status. Not since 1983 had the orange and white been really been good; that was the year Craig Curry’s muffed punt return against Georgia in the Cotton Bowl cost us a certain national championship. Texas finished out of the top 25 rankings each of the next six seasons. In three of those, we had a losing record and did not even play in one of those piss-ant bowl games. Coach Fred Akers, needless to say, was fired. But the easy-going McWilliams did not seem to be the answer, either. Had he not won in 1990, he would have been out as well. A 50-7 loss to Baylor before a Memorial Stadium “crowd” of fewer than 50,000 near the end of the ’89 season did not inspire much confidence.

boots and dusters. It was labeled “They came to restore order to the Southwest.” The sly reference is not to that region of the USA but the now-defunct Southwest Conference. “Order” meant that UT, the biggest and richest school in the SWC, should be king of the hill. But the Longhorns, to my dismay, had fallen to also-ran status. Not since 1983 had the orange and white been really been good; that was the year Craig Curry’s muffed punt return against Georgia in the Cotton Bowl cost us a certain national championship. Texas finished out of the top 25 rankings each of the next six seasons. In three of those, we had a losing record and did not even play in one of those piss-ant bowl games. Coach Fred Akers, needless to say, was fired. But the easy-going McWilliams did not seem to be the answer, either. Had he not won in 1990, he would have been out as well. A 50-7 loss to Baylor before a Memorial Stadium “crowd” of fewer than 50,000 near the end of the ’89 season did not inspire much confidence.

It was a senior-laden team and one without any real superstars, although Dronett and Richard would go on to respectable NFL careers, that traveled to Penn State for an intersectional battle. When the Horns took a 17-13 win, Gunn boasted rather loudly, “We shocked the world!” The first home game was against Colorado, a team that was supposed to challenge for the national crown. But the Buffaloes had just a tie, a narrow win and a loss to show before coming to Austin. CU beat Texas 29-22 and did in fact go on to win it all. McWilliams rallied the troops, and they proceeded to win the rest of their regular season games—Rice, Oklahoma, Arkansas, SMU, Texas Tech, TCU, Baylor and Texas A&M. (I was at the time writing my second book, “For Texas, I Will” / The History of Memorial Stadium and had season tickets that allowed me the opportunity to watch, up close and personal, on the field. Of course, I attended every home game.) Southwest Conference champions, they had risen to No. 3 in the nation. As only Colorado and Georgia Tech stood before them, improbable as it seemed, the Horns had a genuine chance to win their first national championship since 1970, when Darrell Royal ruled the roost. All they had to do was beat the University of Miami, as convincingly as possible, and hope the Buffs and Yellow Jackets lost. Stranger things had happened.

The Canes come to Dallas with bad intent

The Hurricanes’ recent pigskin proclivities were positively prodigious: national crowns in 1983, 1987 and 1989, with very close calls in 1986 and 1988. Dennis Erickson’s 1990 group of scholar-athletes had lost to Brigham Young and Notre Dame but was still ranked No. 4. To say that “the U” carried a reputation would be putting it lightly. They were reviled by many college football fans—though certainly not their own—for being brash, having lengthy rap sheets and wearing military fatigues before games to emphasize that these were not athletic contests but wars. These were fights to the death! Since the announcement of the Texas-Miami Cotton Bowl three weeks earlier, the Canes had been uncharacteristically quiet. When Thomas opined that many of them were “thugs” and predicted a 28-10 UT victory, there was no response.

The Hurricanes’ recent pigskin proclivities were positively prodigious: national crowns in 1983, 1987 and 1989, with very close calls in 1986 and 1988. Dennis Erickson’s 1990 group of scholar-athletes had lost to Brigham Young and Notre Dame but was still ranked No. 4. To say that “the U” carried a reputation would be putting it lightly. They were reviled by many college football fans—though certainly not their own—for being brash, having lengthy rap sheets and wearing military fatigues before games to emphasize that these were not athletic contests but wars. These were fights to the death! Since the announcement of the Texas-Miami Cotton Bowl three weeks earlier, the Canes had been uncharacteristically quiet. When Thomas opined that many of them were “thugs” and predicted a 28-10 UT victory, there was no response.

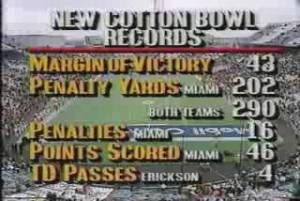

Now, the party. All of my friends and all of Kathleen’s were invited, and quite a few came. On one wall of her living room, I taped the front page of the Austin American-Statesman’s sports section for each Texas game. We had food and drink in abundance, but the effervescent mood changed quickly as UM jumped to a 19-3 halftime lead. Some party-goers had already left. It only got worse after intermission as Gardere (sacked eight times that day) threw an interception that was returned 34 yards for a touchdown. A few minutes later, Craig Erickson—no relation to the coach—connected with Randal Hill on a 48-yard TD strike. Not content to score in a big game on national TV, Hill ran all the way up the Cotton Bowl tunnel. Coming back down, he pretended to pull out guns and shoot them at the Texas players while  doing a gyrating dance. The final score was a murderous 46-3, and I don’t think another soul was left in Kathleen’s house besides me and her. There were also lots of empty seats in Dallas’ venerable stadium well before the game ended.

doing a gyrating dance. The final score was a murderous 46-3, and I don’t think another soul was left in Kathleen’s house besides me and her. There were also lots of empty seats in Dallas’ venerable stadium well before the game ended.

The trash-talking Hurricanes had run roughshod over UT, getting penalized 16 times (nine of those for personal fouls or unsportsmanlike conduct) for a record 202 yards. With the exception of Thomas, who generally stood and fought, our guys seemed intimidated and behaved like weaklings whose lunch money had been stolen on the playground. The Miami coaches insisted they had tried to control their players once the rout was on, all to no avail. In the days and weeks that followed the 1991 Cotton Bowl, the Canes were blistered in the media. Amid a torrent of criticism, the NCAA passed a rule—dubbed the “Miami rule”—whereby a 15-yard penalty could be administered for taunting or excessive celebration. Although I do not recall any comparison being made, it surely resembled something that had happened 19 years earlier. On January 25, 1972, the University of Minnesota basketball team was losing a key Big 10 game to Ohio State when a number of players, including future major league baseball star Dave Winfield, perpetrated a violent, neo-racist (each of the attackers was black, and each of the attackees was European-American) assault on the Buckeyes.

UT football in decline

The 1991 Cotton Bowl left UT fans moaning like a sinner on revival day. The Horns went 5-6 the next year, and McWilliams was canned. John Mackovic came in and did his best for six up-and-down seasons. The golden era of Mack Brown, Ricky Williams, Vince Young and Colt McCoy started in the late 1990s. Only then were the Longhorns back in their rightful place at or near the top.

All the bashing of the Miami football program fell on deaf ears in south Florida as the Hurricanes went 12-0 in 1991 and won another national championship. They did it yet again in 2001.

Add Comment