The Seoul subway system—not all of it underground—is enormous, and that is how I got to Seonghwan on this early spring morning. Line 2 to Line 4 to Line 1, and there I was. A city of 30,000 people, it sits on the northern edge of South Chungcheong Province. Some friends were perplexed about my decision to visit Seonghwan; others admitted they had never even heard of the place. I had my reasons. I was also determined to see a nearby town, Anjung.

I visit the library

We pulled into Seonghwan Station before 11, and things looked promising. I was in the middle of the city and had my choice of accommodations. I went with Hotel Kara (45,000 won). Lacking any kind of tourist map, I had to start with aimless wandering. Finally, I entered a pharmacy and talked to a mask-wearing woman; fine dust from China has been particularly bad in recent weeks. I showed her some papers I had printed out from the Internet. They pertained to a pair of military engagements, one on water and one on land, that had happened nearby in 1894. Claiming no knowledge of the Battle of Pungdo or the Battle of Seonghwan, she suggested I visit the Seonghwan Public Library.

(Before going any further, I want to state that maybe Seonghwan should consider investing in a historical museum and asking the government to install a tourist booth close to the railroad station.)

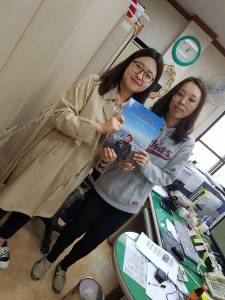

The situation at the library was fairly amusing. I interrupted a young woman—perhaps a librarian, perhaps a staffer—eating her lunch. She put it away and did her best to help me, our language gap  notwithstanding. I do not exaggerate in saying that she devoted more than an hour to research on her computer, phone calls (twice I was put on the line with a bilingual person) and consultations with two colleagues. None of these sweet and intelligent people had ever heard of the aforementioned battles. They and I finally concluded that there was nothing like a public marker indicating what had transpired 124 years earlier. Before I left, I signed a copy of A Seoul Miscellany and donated it to the Seonghwan Public Library.

notwithstanding. I do not exaggerate in saying that she devoted more than an hour to research on her computer, phone calls (twice I was put on the line with a bilingual person) and consultations with two colleagues. None of these sweet and intelligent people had ever heard of the aforementioned battles. They and I finally concluded that there was nothing like a public marker indicating what had transpired 124 years earlier. Before I left, I signed a copy of A Seoul Miscellany and donated it to the Seonghwan Public Library.

The Japanese and Chinese fight on Korean land

Allow me to summarize. In the final decade of the 19th century, Korea was quite weak—politically, economically and militarily. China wanted to retain its centuries-old suzerainty, but Japan had other ideas. On July 23, 1894, Japanese soldiers invaded Gyeongbok Palace in Seoul and established a new regime. A naval battle took place in Asan Bay (just north of Seonghwan) two days later. Koreans could only stand by and watch as the fate of their country was determined by outsiders. The Japanese won conclusively, and it was more of the same on July 29 in Seonghwan. The Japanese, under Major General Oshima Yoshimasa, prevailed as the Chinese—other than those 500 killed—fled in headlong retreat. Han (a feeling of sadness or sorrow, caused by injustice, persecution and/or helplessness) has been the subject of entire books, and a foreigner like me should not pontificate about it. But I can safely surmise that the events of 1894 brought the natives a deepened sense of han.

I still had much of Saturday left, so I ventured to the Seonghwan bus terminal and asked for a ticket to Anjung, 20 kilometers away. No bus goes there, I was told, so I had to go to Pyeongtaek and then  transfer. Fine. I went to Pyeongtaek (a place I had visited in April 2009) and then further west to Anjung. Why, you ask? In 1919, the colonial Japanese built a rudimentary airport there. Mitsubishi Zeros—best known today for their use in kamikaze operations—flew in and out during World War II. It was expanded and heavily used during the Korean War. The renamed Desiderio Air Field, part of the U.S. military’s Camp Humphreys, is the site of 50,000 takeoffs and landings every year. Since the Americans have pulled back from the DMZ, many of them are now at Pyeongtaek and Anjung. Oddly enough, I found very few soldiers, domestic or foreign, during my 2 ½ hours in Anjung. To be honest, I saw just stores, high-rise apartment complexes and a park while there.

transfer. Fine. I went to Pyeongtaek (a place I had visited in April 2009) and then further west to Anjung. Why, you ask? In 1919, the colonial Japanese built a rudimentary airport there. Mitsubishi Zeros—best known today for their use in kamikaze operations—flew in and out during World War II. It was expanded and heavily used during the Korean War. The renamed Desiderio Air Field, part of the U.S. military’s Camp Humphreys, is the site of 50,000 takeoffs and landings every year. Since the Americans have pulled back from the DMZ, many of them are now at Pyeongtaek and Anjung. Oddly enough, I found very few soldiers, domestic or foreign, during my 2 ½ hours in Anjung. To be honest, I saw just stores, high-rise apartment complexes and a park while there.

Passionate Nation

What I did see, in Seonghwan, was many non-European foreigners. Not a female among them, as far as I could tell. There was a restaurant devoted to halal food and an international mart. I wonder what these guys do since there is no heavy industry in the area. I decided to forego a halal meal, opting for shrimp and rice at a Chinese restaurant. While there, I read 10 pages of Passionate Nation / The Epic History of Texas by James L. Haley.

The next morning, I got up and walked to the nearby Angel-in-Us coffee shop and had a café latte. Seonghwan Central Presbyterian Church would soon open for its Easter service. I had met Dong Sung-won there on Saturday and promised him I would attend, despite my casual attire. While sipping my coffee, I looked across the street and saw a rotating set of Jehovah’s Witnesses. There is no need to go into detail about this Christian sect, but they are nothing if not devoted. They stand quietly, smiling at whoever makes eye contact, ready to talk and show literature. I had noticed them out in force in Pyeongchang and Gangneung during the recently concluded Winter Olympics. If they got any “business” during my 90 minutes in the coffee shop, I missed it. For that reason alone, I walked up to one of the men, shook his hand and asked for a JW pamphlet. As a mainstream Christian, though, I am not a likely convert.

The next morning, I got up and walked to the nearby Angel-in-Us coffee shop and had a café latte. Seonghwan Central Presbyterian Church would soon open for its Easter service. I had met Dong Sung-won there on Saturday and promised him I would attend, despite my casual attire. While sipping my coffee, I looked across the street and saw a rotating set of Jehovah’s Witnesses. There is no need to go into detail about this Christian sect, but they are nothing if not devoted. They stand quietly, smiling at whoever makes eye contact, ready to talk and show literature. I had noticed them out in force in Pyeongchang and Gangneung during the recently concluded Winter Olympics. If they got any “business” during my 90 minutes in the coffee shop, I missed it. For that reason alone, I walked up to one of the men, shook his hand and asked for a JW pamphlet. As a mainstream Christian, though, I am not a likely convert.

Easter 2018

Seonghwan Central Presbyterian Church was founded in 1964, although the present building was erected 22 years later. Needless to say, I was an oddity. How often do foreigners visit? It doesn’t matter. I was there among like-minded people. I stood when they stood, bowed my head when they bowed theirs and so forth. I put 10,000 won in an envelope and gave it over. As is the custom, a bountiful meal was  served downstairs after the service. My dining companion was Mr. Dong. Later, we took some photos outside the church and then it was time for me to say, “안녕히 가세요” (annyeonghi gaseyo, or “goodbye” in Korean).

served downstairs after the service. My dining companion was Mr. Dong. Later, we took some photos outside the church and then it was time for me to say, “안녕히 가세요” (annyeonghi gaseyo, or “goodbye” in Korean).

Before getting back on the subway, however, I took 30 minutes to walk through the Seonghwan Traditional Market, held the first day of every month since 1914. I saw food, of course, plus clothing, light industrial tools and a couple of fortune-tellers. I bought some fruit and nuts for my usual breakfasts back in Seoul.

6 Comments

Hi Richard-What an interesting weekend you had! I enjoyed the article. I found it interesting that “han” is Korean for sadness caused by injustice and is also the dominant race in mainland China, the Han Chinese. Hmmm… Kevin

Thanks for your comment, Lt. Nietmann. I wonder whether there is any connection between those two words.

Richard – it is always a joy to read about your various and strategically-planned excursions around Korea. I’m grateful for you allowing us to live the experience vicariously through your essays, each of which are very well written, indeed. Hope all is well!

Ah Justin, my friend in far-distant Austin, TX!! Thanks for reading it and for your comment.

Hello. Teacher. I fully enjoyed your writing. It seems you had a special Eastern Day. Looking forward to reading your next writing.

Thank you, Bomin. Keep up the good work in Greeley, CO….so very proud of you!!

Add Comment