There is a fundamental difference between receiving an invitation to somebody’s house, and just walking up and knocking on the door. In the first case, you will most likely be invited in and treated with a measure of respect. While that’s possible in the second case, you may also find that the door remains  closed or the homeowner is perturbed about being intruded upon. Such a set of scenarios, I believe, applies to high school football players who are recruited and given scholarships vis-à-vis those who try out and hope for the best.

closed or the homeowner is perturbed about being intruded upon. Such a set of scenarios, I believe, applies to high school football players who are recruited and given scholarships vis-à-vis those who try out and hope for the best.

If you go back far enough in the history of college football, all players were walk-ons. Every football program from Adelphi University to Zebulon Pike College (OK, I made that up since none start with “Z”) commenced with whatever young men were already on campus; as the decades went by, high school athletes found their way to the successful schools or were recruited by means ethical or otherwise. In the 1920s and 1930s, it was not uncommon for the star quarterback to earn money for tuition, books, room and board by pushing a broom or some other lowly job. The purists hated it; we had begun moving down a gradual and slippery slope.

My focus is southern schools in the mid-1950s through the late 1960s and their reluctance to give athletic scholarships to African-American players, the same as with European-American players. The administrators, faculty, alumni and students were overwhelmingly—if not totally—European-American, and in those racially fraught days “caution” was ever the watchword. From Texas to Maryland, integrating the football team was not easy. Warren McVea of Houston, Jerry LeVias of SMU, Lester McClain of Tennessee, Leonard George of Florida and Marion Reeves of Clemson, for example, were recruits. All were given scholarships and told, in essence, “we want you here.” The same cannot be said about the earliest black walk-ons. Insufficient attention has been paid to the role of walk-ons in this process, something I endeavor to rectify. The following list, I must emphasize, is anything but complete. Furthermore, who knows how many asked to walk on and were either dissuaded or flat-out refused?

about the earliest black walk-ons. Insufficient attention has been paid to the role of walk-ons in this process, something I endeavor to rectify. The following list, I must emphasize, is anything but complete. Furthermore, who knows how many asked to walk on and were either dissuaded or flat-out refused?

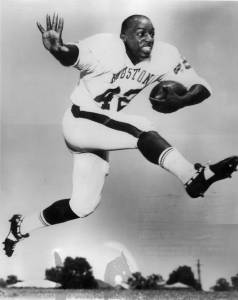

- It started with Ben Kelly at San Angelo College (now Angelo State University) in 1953. He was a native of San Angelo, having attended the city’s segregated high school. Kelly introduced himself to coach Max Bumgardner and to the president, Rex F. Johnston. Johnston phoned the registrar’s office. Simple as that, the school was integrated and the football team along with it. Kelly was a two-time all-Pioneer Conference running back for the Rams. He played one season each with the San Francisco 49ers and New York Giants, where his coaches included Vince Lombardi and Tom Landry.

- Since I have written so extensively about Abner Haynes at North Texas State, I will just say that he walked on with the Eagles in 1956 and by the end of his senior year (1959) he was surely the finest player in school history. Haynes deserves inclusion in the College Football Hall of Fame, and his credentials for the Pro Football Hall of Fame are strong as well.

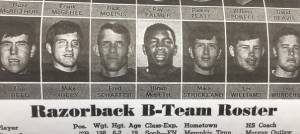

- I have also covered Darrell Brown, who walked onto the Arkansas freshman football team in 1965 and had a harrowing experience in Fayetteville. Three years later, Hiram McBeth, a defensive

back from Pine Bluff, did the same. His teammates and coaches with the 1968 Shoats were scarcely more welcoming than Brown’s had been, but he survived. McBeth took part in the 1969 Red and White game, and was on the varsity “B” squad the next season. Two years he labored out of the spotlight, but he made the varsity—the real thing, Frank Broyles’ Razorbacks—in 1970. UA had another black walk-on, Jesse Kearney, a fullback/linebacker, in 1969.

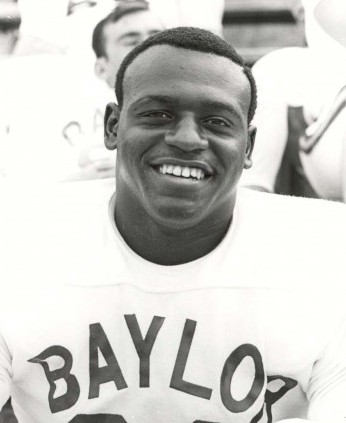

back from Pine Bluff, did the same. His teammates and coaches with the 1968 Shoats were scarcely more welcoming than Brown’s had been, but he survived. McBeth took part in the 1969 Red and White game, and was on the varsity “B” squad the next season. Two years he labored out of the spotlight, but he made the varsity—the real thing, Frank Broyles’ Razorbacks—in 1970. UA had another black walk-on, Jesse Kearney, a fullback/linebacker, in 1969. - John Westbrook, the son of a preacher man, told Baylor coach John Bridgers in 1965 of his experience at Elgin’s all-black Washington High School. BU had barely integrated its student body, and already one of them wanted to be on the football team! Bridgers was unfazed. He welcomed Westbrook to the Bears program, although some of his assistant coaches and players sought to discourage him. Despite winning a scholarship, he battled depression and pondered suicide. Westbrook, a running back, was a three-year varsity letterman. Each year since 2009, Baylor has handed out the John Westbrook Award for Courage and Perseverance, one each to a male and female athlete.

- The 1967 Texas freshman team had two black walk-ons: Robinson Parsons and E.A. Curry. The latter caught a touchdown pass against the Rice frosh, a fairly significant fact.

Leon O’Neal, UT’s first black signee, played for the Yearlings the next season; he soon left due to poor grades, however. Curry stuck it out and was actually a member of the 1968 varsity. But—my sources are vague on this—he was apparently not on the traveling squad. Curry donned a uniform, took part in pregame warmups and stood on the sideline during the Houston, Oklahoma State, Arkansas, SMU and Texas A&M games at Memorial Stadium, but Darrell Royal never thought to give him any game action. Talmadge Blewitt walked onto the 1969 UT freshman team, too.

Leon O’Neal, UT’s first black signee, played for the Yearlings the next season; he soon left due to poor grades, however. Curry stuck it out and was actually a member of the 1968 varsity. But—my sources are vague on this—he was apparently not on the traveling squad. Curry donned a uniform, took part in pregame warmups and stood on the sideline during the Houston, Oklahoma State, Arkansas, SMU and Texas A&M games at Memorial Stadium, but Darrell Royal never thought to give him any game action. Talmadge Blewitt walked onto the 1969 UT freshman team, too. - Sammy Williams, a receiver from Houston, walked on at Texas A&M and was a member of the varsity in 1967—the season the Aggies won the Southwest Conference title. Coach Gene Stallings, who had said two years earlier that A&M was “not ready” to

integrate its football program, never let him into a single game. James Reynolds, Mike Bruton and Hugh McElroy were also early walk-ons at A&M.

integrate its football program, never let him into a single game. James Reynolds, Mike Bruton and Hugh McElroy were also early walk-ons at A&M. - In February 1967, Dock Rone made a courtesy call to the office of Paul “Bear” Bryant, the coach at Alabama. Rone explained that he had played high school ball in Montgomery and wanted to go out for the team. The way Rone tells it, Bryant expressed admiration for his courage but offered no immediate answer. He made a few phone calls (perhaps seeking information, perhaps issuing directives, but who knows?) before agreeing to give the young man a chance. In fact, Rone would not be alone in spring practice in Tuscaloosa. Andrew Pernell, Arthur Dunning, Melvin Leverette and Jerome Tucker entered a silent locker room, put on helmet and pads, and went out on the field to knock heads with their European-American teammates. Rone and Pernell played in the Crimson and White game, managing to hold their own. Pernell’s experience mirrored those of the above-mentioned Curry (UT) and Williams (A&M) in that he was a member of his school’s varsity team in 1967 but he never got into a game. Like many of the other African-Americans listed here, Rone has been honored and recognized in countless ways. In interviews with European-American reporters, he takes pains to emphasize that he was not trying to make a social or political statement. He just wanted to play college football.

8 Comments

Zacharie School of Real Estate, Zarem Golde Ort Technical Institute, Zemlocks Helicopter Service, Zion Bible Institue, Zittel School of Real Estate, and Zoe College, Inc, are very unhappy with you!

I admire those guys for trying out, that had to be really tough and not rewarding.

Hahahaha believe it or not, Kenny, I looked those up too! But I dont think any of them have ever had football programs. Thanks as always for reading and commenting.

Hi Richard. I’ve always loved this topic. Back in “the day” blacks weren’t given a chance and weren’t taken seriously. Jim Brown threatened to quit the Syracuse football team many times. W.E.B. Dubois wrote, “To be a poor race in a land of dollars is the very bottom of hardships.” Anthropologists findings at the time gave way to whites being the smarter, superior race. Darwinists believed blacks weren’t only mentally inferior, but also physically inferior to whites. Thank God that’s been disproven. Good work!

Thanks, big fella. We are on the same team!

I’ve always been a big fan of Abner Haynes and I surely applaud your efforts into getting him in the college and pro football hall of fame. I wish the higher-ups would have listened…

You are an Abner fan?? Me too! I love this guy, both as a football player and as a human being. His name resonates with me. I urge both halls to admit him ASAP.

People tend to look at the contemporary situation rather than considering the important issue in the past. I learned what happened in the college and football field in the past and crucial issues that we need to keep remind. Thanks for describing and making your great essay.

Thanks for reading and commenting, Bomin! What happened in those days, so long ago, was very curious. We have made some social progress.

Add Comment